PsychNewsDaily Publishers

100 Summit Drive

Burlington, MA, 01803

Telephone: (320) 349-2484

PsychNewsDaily Publishers

100 Summit Drive

Burlington, MA, 01803

Telephone: (320) 349-2484

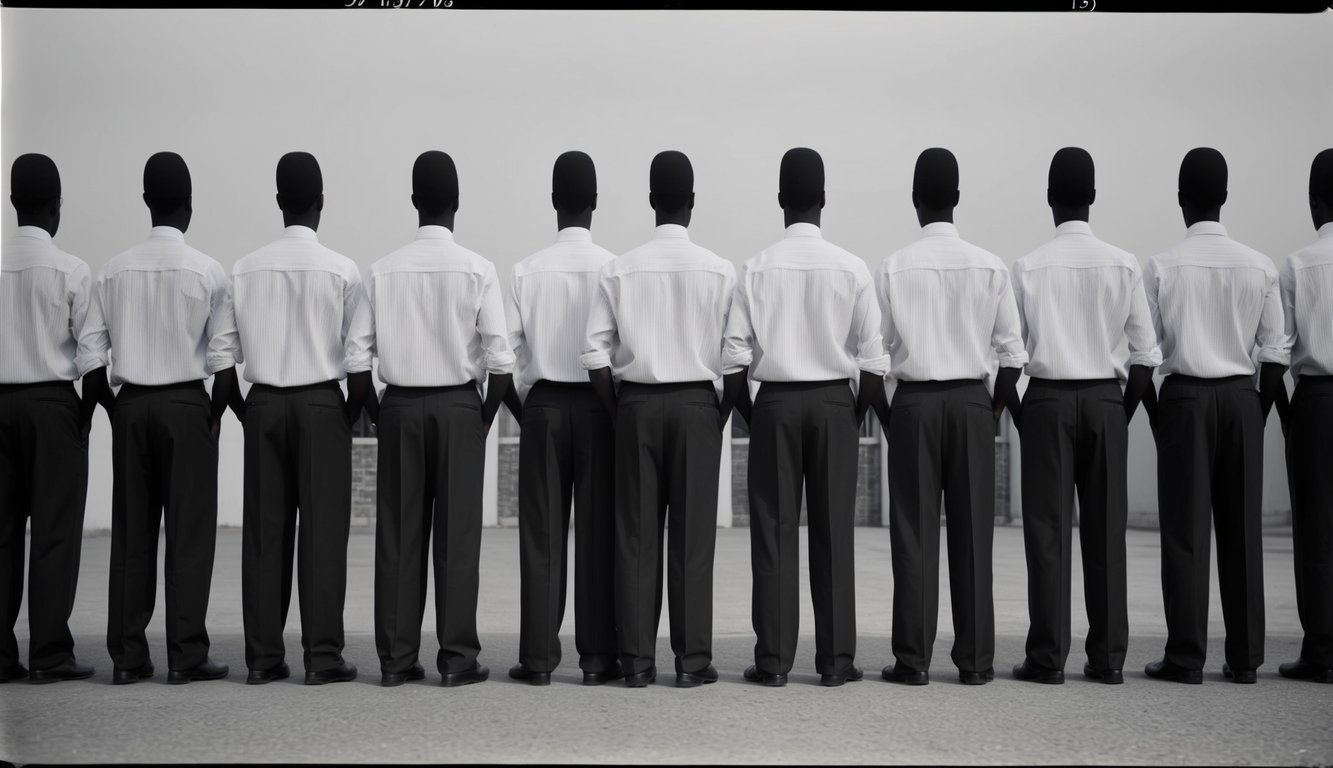

Conformity influences human behavior through social pressures, norms, and group dynamics, impacting beliefs, decisions, and actions across various cultural contexts and life stages.

Conformity significantly impacts human behavior and social dynamics. It affects our beliefs, choices, and actions within social groups and broader society.

Conformity describes the inclination of individuals to adjust their attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to align with those of a group or society. This psychological phenomenon stems from social pressure, the pursuit of acceptance, or the belief that others’ actions are correct.

Conformity can take various forms, ranging from simple fashion choices to the embracing of complex ideologies. While it is essential for fostering social order and cohesion, excessive conformity can result in negative consequences.

Several factors that influence conformity have been identified by psychologists, including:

The exploration of conformity gained prominence in the mid-20th century. Muzafer Sherif conducted autokinetic effect experiments in the 1930s, establishing a foundation for understanding how individuals adhere to group norms in ambiguous contexts.

Solomon Asch’s pioneering conformity experiments during the 1950s revealed that individuals often conform to incorrect group judgments, even when the correct answer is obvious. This research underscored the substantial influence of social pressure on personal decision-making.

Additional notable experiments include Stanley Milgram’s obedience studies and Philip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment, which further delved into the depths of human conformity and its potential implications.

Psychologists typically identify three major types of conformity:

Compliance: Individuals superficially conform to group norms while privately dissenting.

Identification: Individuals conform to gain the approval of a group or an admired person.

Internalization: The most profound type of conformity, where individuals fully adopt group beliefs as their own.

These types of conformity can be observed in various social contexts, spanning peer groups to workplace environments. Understanding these distinctions clarifies why individuals conform under different circumstances and to varying extents.

Conformity intricately influences social interactions and group behaviors. It affects how individuals assimilate into social norms and react to group pressures across various cultural backgrounds.

Social influence is crucial in shaping individual behaviors within groups. Group norms establish unspoken rules and expectations among members, significantly impacting decision-making and actions.

Individuals often conform to uphold social harmony and evade rejection. This inclination can yield both beneficial and detrimental results; while conformity can facilitate cooperation and social unity, it may also restrict creativity and independent thought.

Social psychologists differentiate between two primary types of conformity:

The number of individuals in a group can greatly affect levels of conformity. Larger groups typically exert greater pressure for individuals to conform, a phenomenon known as the Asch effect, after psychologist Solomon Asch.

Group pressure manifests in various ways:

As group sizes increase, individuals may feel a stronger compulsion to align with the majority. This effect is particularly pronounced in public situations where standing out can invoke anxiety.

Cultural distinctions significantly affect conformity behaviors. Collectivist and individualistic cultures exhibit divergent patterns of conformity.

Characteristics of collectivist cultures include:

Contrastingly, individualistic cultures typically:

Understanding these cultural variances is vital to interpreting conformity behaviors in diverse contexts.

Conformity plays a significant role in shaping individual behavior through various psychological dynamics and societal influences. Its manifestations vary across different age groups and can differ between public and private scenarios.

Varieties of conformity behavior can be classified into internalization and compliance. Internalization is when individuals sincerely adopt the beliefs or actions of others, blending them into their personal value system, often resulting in lasting changes in attitudes and behavior.

In contrast, compliance entails outward agreement without altering one’s private convictions. It’s frequently motivated by the desire to prevent conflict or secure social acceptance. Consequently, individuals may outwardly conform while holding private beliefs that differ.

Informational conformity takes place when individuals seek guidance from others in uncertain contexts, while normative conformity arises from the wish to be accepted and to avoid rejection. Both forms can have a substantial effect on individual behavior.

Patterns of conformity evolve throughout a person’s life. Children frequently conform to their parents’ expectations and peer influences. The adolescent years are often characterized by heightened conformity to their peer groups, as teenagers endeavor to establish their identities and be accepted.

Adults tend to exhibit more selective conformity, balancing social expectations with their personal beliefs. Factors such as intelligence can affect an individual’s likelihood to conform. Furthermore, older adults may display reduced conformity in certain areas as they gain confidence in their identities.

Research indicates that conformity tends to peak during adolescence and early adulthood before gradually decreasing with age. Nonetheless, situational factors can significantly influence conformity behavior at any stage of life.

Public conformity refers to observable changes in behavior occurring in the presence of others, often driven by social motivations such as the pursuit of prestige or acceptance. Individuals may outwardly align with a group while privately holding different beliefs.

Private conformity involves adopting group norms even in solitude. This form can engender more profound and enduring shifts in attitudes and behaviors.

Recognizing the distinction between public and private conformity is essential for understanding social influence dynamics. Some individuals may show high public conformity but low private conformity, while others may completely internalize group norms in both contexts.

Conformity profoundly influences human behavior and societal interactions, involving intricate psychological mechanisms and social dynamics that shape individual choices and enhance group unity.

People conform for multiple reasons. Social pressure frequently compels individuals to align with group norms, driven by the desire to belong and avoid rejection.

Awareness of the risks of standing out or making errors further contributes to conforming behavior. In uncertain environments, individuals often look to others for direction, leading to informational conformity.

Moreover, some conform to receive social endorsement or maintain relationships, with normative influence being particularly potent in collectivist cultures that prioritize communal harmony.

Conformity can profoundly affect one’s sense of self, as individuals may grapple to reconcile their authentic identities with external social expectations.

In individualistic cultures, excessive conformity may carry a negative connotation, implying a deficiency in independence or originality. However, some degree of conformity is often necessary for social integration.

The pressure to conform can instigate cognitive dissonance when personal beliefs are misaligned with group norms, leading to attitude shifts or justification of conformist actions.

Non-conformity symbolizes a rejection of social norms and expectations, driven by the desire for uniqueness, self-expression, or principled dissent against mainstream attitudes.

Psychological differentiation contributes to non-conformist tendencies. Individuals possessing a strong sense of self may be more resilient against social pressures.

Non-conformity can incur social repercussions, such as ostracism or criticism. Nevertheless, it also has the potential to promote innovation and societal advancement by challenging conventional norms.

Striking a balance between conformity and independence is essential for psychological well-being and social functionality. This equilibrium allows individuals to remain authentic while navigating societal expectations.

Conformity influences a multitude of aspects of human behavior and social interactions. Its effects can be observed in workplace dynamics, personal relationships, and decision-making processes.

Workplace norms depend greatly on conformity to sustain order and productivity. Employees frequently modify their behaviors to align with corporate culture, potentially enhancing efficiency and teamwork.

Conformity also influences dress codes and communication methods. Adhering to these norms can strengthen professional image and client rapport.

However, excessive conformity risks stifling creativity and innovation. Organizations should aim for a balance that preserves standards while welcoming diverse viewpoints.

Adhering to social norms can improve interpersonal relationships by helping individuals adeptly navigate social interactions and forge stronger connections.

Adjusting to group expectations can alleviate social anxiety and foster a sense of belonging, contributing positively to overall well-being and mental health.

Conversely, consistent conformity can suppress authentic self-expression. Balancing conformity with individuality is vital for fostering genuine relationships and supporting personal development.

Conformity may sometimes lead to adverse outcomes. For instance, the bystander effect occurs when individuals fail to assist in emergencies due to social pressure.

Groupthink represents another detrimental effect, where prioritizing group harmony undermines critical thinking and leads to poor decisions. Groups may overlook crucial alternatives or risks.

Peer pressure can induce harmful behaviors, especially among young people, potentially resulting in risky activities or substance abuse to gain acceptance within a peer group.

Excessive conformity might also hinder individual growth and creativity, contributing to a diminished sense of identity and eroded self-esteem over time.

“`